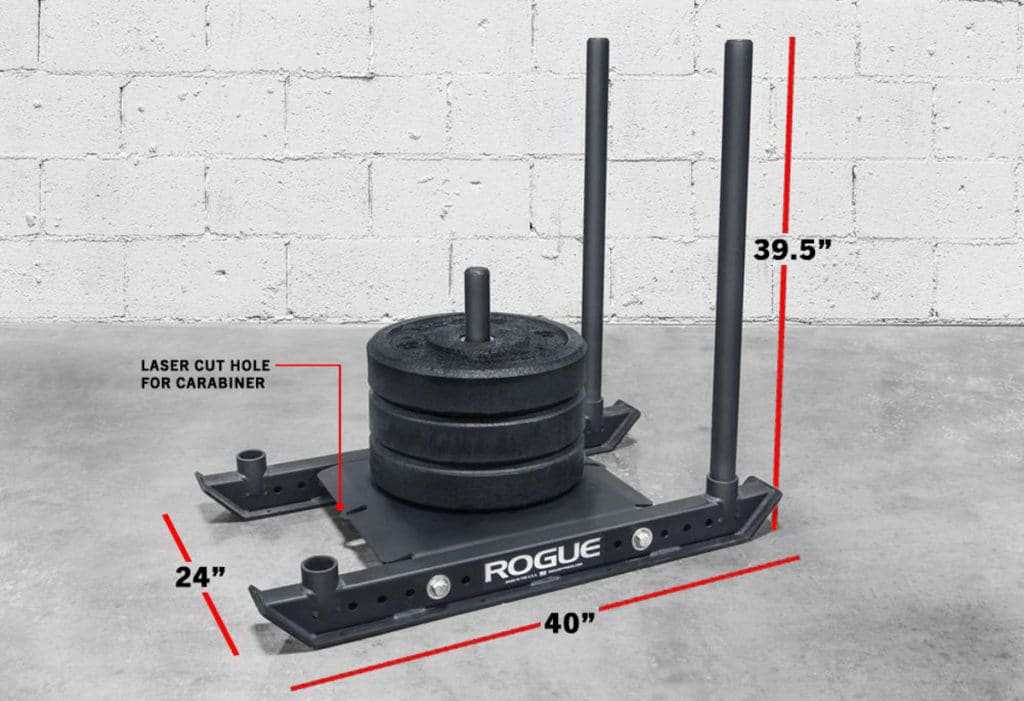

Equipment shopping for the opening of our first large clinic space was a treat. For a strength junky like me, it was a blank check to get anything I could have ever wanted. Within the first year of being in that space, I realized several things. Just because we had the equipment, does not mean that patient’s would have access to that equipment. When it comes to Movement Based Medicine, repetition and consistency are key. Having the perfect piece of equipment accessible only at our clinic is somewhat useless. This created a massive house cleaning to remove equipment that did not have significant returns for patients when used only in clinic. One such piece of equipment was the Rogue Dog Sled. When it comes to lower body rehabilitation, organic pushing and pulling motions still rank number one in my book. It is very challenging to artificially create the full body balance that pushing or pulling a heavy object can. Pulling a heavy sled backwards is my top tier choice for knee rehabilitation, especially for instability. This would require consistent use though and increased loading. But, alas, they are rarely in any gym let alone a common commercial gym that most patients will be using. So I decided to trade more open space for the footprint of the sled.

I had help loading it into our camper van and that was a very easy process. It lived in the van for several days because I would get home late and simply not want to bother Whitney with the task of moving it. One random morning I decided I got sick of the potential wasted fuel hauling that thing around and unloaded it myself before heading into the clinic. What happened next was a combination of good and poor decision making. First, I very clearly hinged from my hips as is my natural pattern these days. Because the sled was rather large in size and at an unusual height it was impossible to keep a straight spine. As I have said many times, I believe life (and sport) is never perfect and that the decision to load larger structures like your hips is more important than the shape of your spine. Second, I assumed the sled, despite its foot print and ridiculous over engineering, would be a paperweight to me. There was no doubt in my mind that picking it up would be a simple task because I am oh-so strong.

Upon actually lifting the sled many thoughts cystralized in my head in the matter of milliseconds:

“Oh s*$! this is heavy.”

“Geeze, I almost hurt my back.”

“I am glad I have surplus.”

“I should have waited for help.”

The sled weighs 102 lbs without the optional bridge attachments, plastic skis, and wrap around rail. I would guess that adds another 20 lbs easily if not more. It is also 40” x 24” in its footprint with awkward handling points. All that combined made it feel more like 275 lbs and my body was acting as if it was about to pick up a 55lb kettlebell. The strain to the ligaments and muscles of my low back was immediate despite my hips firing at full output. The rounded shape of my spine and the height of the van floor made it impossible for my low back not to take some load. The act of lifting the sled was all relatively quick and left me genuinely worried about putting it back down. I walked into our garage and braced as hard as I could as I slid it down my body to the ground which seemed lower than it had ever been.

I assessed my body to feel a mild sprain of my right sacroiliac joint and a subtle sprain to some lumbar ligaments. I also assessed my clinic clothing to find that, amazingly, they were completely fine. I was lucky on two counts.

This story highlights why most rehabilitation programs are not enough and why we train for what we call surplus. A low back injury or, even worse, a disc herniation is the result of thousands of erroneous movements leading to small injury. Compounded over thousands of cycles, the damage eventually outpaces the repair and an injury happens. A faulty pattern has allowed a person to destroy what is genuinely an extremely well made and dense structure in the human body. Because of this you must replace the old movement pattern with a new one before any healing can occur. You then need to force the body to automate and adapt to that new system. The default pattern must become one that is anatomically viable. This is why we train patients to such high standards, especially if they have had a disc injury. Reaching a deadlift of 1.25 times bodyweight (an expectation of all patients) requires repetition and consistency over a relatively long time frame. The months of training to achieve this force the body to adapt with new ligament density as well as create hundreds of cycles of a new pattern. It effectively erases the old pattern which created damage and replaces it with a new pattern that creates strength.

This is massively important because life is not always perfect or ideal positions. Things happen! There is no doubt in my mind that if it were not for years of training that I could have seriously hurt myself. There is also no doubt that I was being an idiot by letting my ego be so casual about the task and so inflated about my strength. This is not the only life example in which I have felt this. Each year there are several moments where the same situation happens and I again remain thankful for all my training. Surplus is why training in an artificial environment translates to real life.

Be thankful for Surplus.