Very frequently when patients visit Move Better, they are experiencing pain in a specific area that may be a result of compensation elsewhere in the body. When I say that everything in the body is connected, I promise that I mean this in a literal sense. In the context of musculoskeletal medicine, outside of a fracture or dislocation (which are also both problematic by the way) all of the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments are connected together through a complex network of fascial planes and connective tissue structures.

A good model for thinking about how the body is structured is to imagine a large building with a support beam removed from one corner of the building. The area where the beam is removed will cause the structure above to collapse. Very similarly, in the human body, if there is a region of compensation or overload in a particular joint, muscle, or connective tissue structure, this can lead to a compensatory movement or position in attempts to restore balance to the system.

A recent patient of mine served as a good example of this coming into the clinic with knee pain. Outside of direct trauma/acute injury to the knee, typically the knee acts as a point of compensation either from above or below that joint. With this specific patient, their foot was collapsing which was pulling the knee inward towards the collapsed arch. This compensation is referred to as “knee valgus” and was causing pain felt on the inside of the knee where the tissues were being exposed to a consistent stretched position. When this patient would squat during workouts the knee would collapse inward even more and exacerbate the knee pain.

This patient received relief by focusing on strengthening the muscles that kept the foot in a more neutral position, strengthening the hip muscles that keep the knee stable, and then applying the strength of these new positions to more complex movement patterns reflective of daily activities. By allowing for the ankle to rest in a more structurally balanced position, the knee no longer needs to make adjustments thus reducing the symptoms of pain associated with the compensation.

Another patient of mine was experiencing low back and neck pain. The most significant finding was an extreme difficulty for them to maintain a posture that did not allow their mid back region to slouch. The spine is composed of different sections that have opposite curves to one another. With what is colloquially understood as “poor posture” we typically have an overexposure to forward rounding in the mid back region. When the mid back is rounded forward, very often the neck or the low back will compensate by arching backwards. This can lead to compressive forces on the neck and back which can lead to muscular as well as connective tissue irritations over time.

With this patient, they were able to reduce the pain they were feeling in their low back by strengthening the muscles in the mid back responsible for helping to maintain an upright posture. We then applied this new postural position to a multitude of pulling exercises, hinging movements, breathing mechanics, and other activities reflecting daily life. By bringing a more neutral position to the thoracic spine and then strengthening the position through movement,the body learns to allow the area experiencing pain to relax and heal.

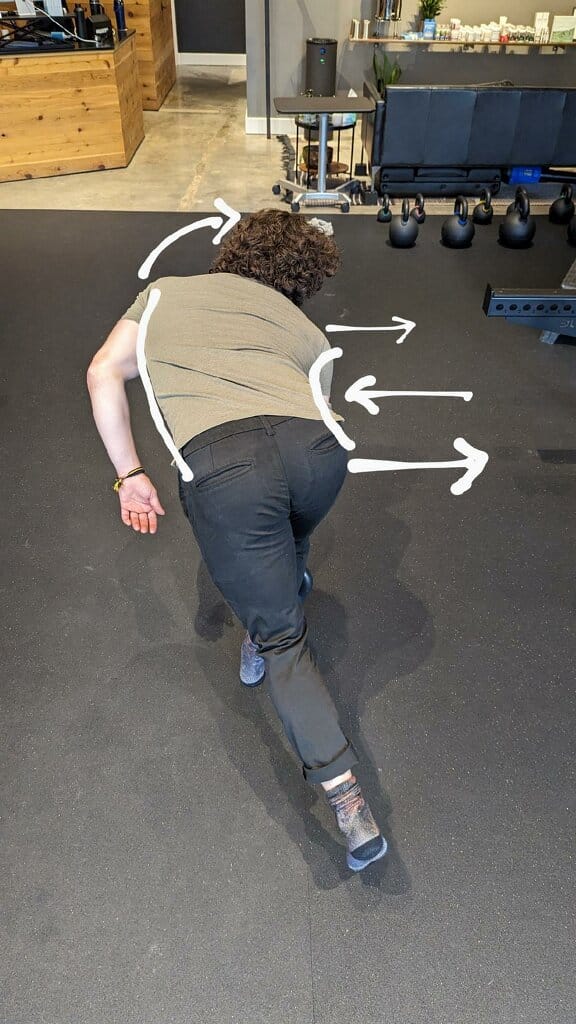

I also recently worked with a patient that came to the clinic for treatment concerning low back/hip pain. The most significant clinical finding was an imbalance in the strength/coordination of his hip muscles maintaining single leg stability. The muscle most associated with stabilizing the side of the hip is the gluteus medius. When the leg is moving independently from the rest of the body, this muscle is thought to be responsible for keeping the hip in a structurally strong position when swinging the opposite leg. Often when this region of the hip is not activating properly through movement, the hip will shift outwards. The kinetic chain can compensate for this by compressing the lower back on the side of hip weakness to help maintain balance.

This patient experienced relief by working on single leg stability exercises targeting their ability to use the relatively weak hip to work independently in a way that did cause excessive lower back movement. We also focused on bracing exercises to help create a solid foundation of stability for them to move their hip from.

The examples listed above are just a few of many kinetic chain compensations we observe, diagnose, and treat in the clinic. I find this to be extremely valuable because conventional wisdom usually guides patients to believe that the area they are feeling pain is the problematic area. This usually leads to a very local approach to pain management consisting of stretching, icing, heating, or applying topical pain relievers to the area that hurts not knowing that the reason WHY the area hurts is because another area they are unaware of is not functioning optimally. Here at Move Better, we take a full body approach to treating pain and are invested in establishing strength, competency, and awareness in areas outside of the painful region to ensure that all the contributing factors to the experience of pain are being accounted for.